HIDDEN HARMONY

(Hidden Harmony page one is here.)

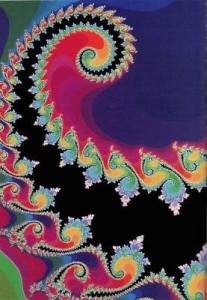

Photo below-Gregory Sams/Photo Researchers Inc.

Would you like to read this article on your KINDLE READER?

IT WAS RAINING HARD WHEN THE ferry left the Lake Champlain landing dock near Plattsburgh, New York, for the 20-minute crossing to Vermont. The plan was to drive by old haunts and to exit from the interstate, as we often had, on Route 100 and follow the rough spine of the Green Mountains 65 kilometres to Rochester, a village situated in the centre of the state.

Earlier that morning I had awakened at our lake house in the Adirondacks feeling that I might be about to take a foolish emotional trip to a past that had held no future. Was this some fantasy designed to overshadow still-undefined personal failings, or perhaps the romantic resurgence of a 52-year-old writer and television producer stoking the bonfire of emotion?

If I could take any comfort, it would be in the realization that for centuries, people have been searching for an understanding of why some places hold certain, ineffable power. The reasons range from the mundane to the mystical. I may feel good in the mountains, for example, because the air lacks pollution and allergens. There may be less oxygen entering the blood, which can, even at moderate altitudes, make humans feel quite different, even lightheaded.

There may also he profound power in expectation. Consider the so-called sacred places, such as Lourdes, the River Ganges, Mayan temples, Gothic cathedrals, Stonehenge, the Great Pyramid of Cheops. Might they be more humbly described as old and cherished places where expectations of magic run unfettered, encouraged by travel brochures and local promotional campaigns?

Can emotions at certain places of magical reputation be enhanced by physical events such as the earth’s electromagnetic impact on the brain? That is what is proposed by neuroscientist Michael Persinger of Laurentian University in Sudbury, who has studied how electromagnetic fields can trigger both subtle and bizarre shifts in the way one experiences the world, ranging from mild mood changes to vivid hallucinations. Persinger also suggests that some brains appear to be more vulnerable than others in reacting to geophysical discharges, possibly originating in tectonic strain within the planet’s crust.

Halfway to Rochester, my dark mood had already dissipated. I had attributed the nervous self-doubt at the outset of the journey to the unpredictable nature of my quest and was slowly becoming more in flow. I was beginning to feel a deep enjoyment of the mountains, of being absorbed into their towering strength and density. As psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi writes of it, flow is a feeling of being connected to something larger than the self. For me, that “something” has often been mountains, particularly the Green Mountains.

Such a medium for flow is not surprising, considering that mountains have been revered the world over. More than a half billion people in southern and central Asia consider the Himalayas sacred. ]apan’s Mount Fuji and Greece’s Mount Parnassus, home to Delphi, are often described as radiating a life energy. Indeed, feng shui, the ancient Chinese effort to understand and harmonize the silent energy flow between humans and nature, portrays mountain peaks as living crossroads of heaven and earth from which all paths of vitality emanate.

What may seem mystical to our culture, however, can perhaps be illuminated by dramatic developments in physics, math, and medicine. When at Harvard Medical School recently, I told Ary Goldberger, a cardiologist and research scientist, that I was planning a trip to the Green Mountains. He speculated that I would likely feel well because of my body’s potential to resonate well with the forest and mountains.

He suggested that the branchings of trees, the jagged features of the mountains- in fact, the full impact of the irregularities of the fine details of the landscape—were similar to patterns in the human body itself. “]ust look at medical textbooks,” he said, “and you’ll notice drawings of treelike branchings of blood vessels and neurons, the intricate patterns of the lymph system, the lungs, muscle tissue. There is likely some deep connection between these internal landscapes of the body and the outside landscapes that we see.”

The patterns he spoke of are often referred to as fractals, geometric patterns with similar detail at many scales that are the products of complicated nonlinear processes. “You can see these tracings of change in nature in the form of coastlines, clouds, and tree and rock formations,” Goldberger explained. If you look through a microscope at brain cells, for example, you can see branches on branches on branches—asymetric fractal—like entities called dendrites. In recent years, Goldberger has paid special attention to the cardiovascular system. He contends that just a changing form of an individual tree is the result of many variables, including soil composition, magnetic fields, and ever-changing weather, so is the integrity of the human heart the result of all bodily activity, as well as stimulation from the external environment.

he spoke of are often referred to as fractals, geometric patterns with similar detail at many scales that are the products of complicated nonlinear processes. “You can see these tracings of change in nature in the form of coastlines, clouds, and tree and rock formations,” Goldberger explained. If you look through a microscope at brain cells, for example, you can see branches on branches on branches—asymetric fractal—like entities called dendrites. In recent years, Goldberger has paid special attention to the cardiovascular system. He contends that just a changing form of an individual tree is the result of many variables, including soil composition, magnetic fields, and ever-changing weather, so is the integrity of the human heart the result of all bodily activity, as well as stimulation from the external environment.

Goldberger has used the computer to analyze intervals between heartbeats and has shown that the tracings of healthy heartbeats exhibit remarkable similarity to fractals in nature, such as the jagged lines of a coastline: the patterns of the heartbeat are varied and thus more adaptable. The patterned beating of an unhealthy heart, by contrast, may become all too regular.

Yasha Kresh, professor of cardiothoracic surgery at the MCP-Hahnemann School of Medicine in Philadelphia, points out that more goes on in the human body than is readily apparent. The irregularity of the healthy cardio-vascular system has an underlying order; that is, the system is highly interactive and possesses many interdependent processes. “Many of the mechanisms we attempt to study in isolation are coupled and function in parallel, and many of the actions/reactions take place simultaneously,” he said. “The heart and circulation operate on multiple time scales or frequencies and vastly distributed space. It is this complexity that allows the system to remain organized. When you lose this interconnectedness— when the system loses — that’s what disease is.”

The force behind these interdependent processes in the body, as in nature, is what scientists refer to as chaos. This is not the type of chaos typically defined in dictionaries as utter confusion, but rather the type now viewed, using the calculating power of the computer, as complex systems in nature that have underlying patterns, even though on the surface they appear unpredictable or random.

One hallmark of chaos theory is that seemingly insignificant changes in the system (whether in nature or in the human body) can lead to bigger changes. As Taoists have imagined, for example, when a butterfly flaps its wings in Canada, it may have some impact on the weather south of the border. In other words, in nature, everything can influence everything else.

Everything matters.

In this context, fractals can be seen as the irregular tracings of self-similar structures of ever finer detail, created as nature shapes itself and evolves, such as in the form of mountain ranges or bodily structures.

Is this seemingly unpredictable exuberance of nature the cause of as much pleasure when we give ourselves a moment to dispose of our selves and connect to the chaotic world?

(Continue to Page Three Here…)